Who #13: Love is a many-gendered thing

"I'm a boy. I'm a boy. I wish I were dead." : Jack Lemmon, SOME LIKE IT HOT

Let’s talk about the Who’s queer energy. Off the charts, if you ask me. I deduced this after two and a half consecutive songs, and the stage schtick did the rest. Sometimes I’m surprised they were allowed to perform in any conventional context. Did the authorities see what they got up to up there? Straight boys and girls don’t act this way. I don’t make the rules.

These are not love songs for women. These songs are so concerned with identity as to render the band’s name a little too on the nose. Identity freak-outs that typically ask one of two questions: Who am I? and Am I a man? The answers to the former are nebulous; the answers to the latter are hardly a resounding ‘yes,’ mostly because the asker struggles to define manhood to begin with and, in the event he does define it, regards it with suspicion.

I am of course not claiming that any of the members of the band have explicitly identified as queer, except Pete, who has, retroactively. But, to cite a great internet historian, you need not call yourself queer to do queer things. Keith Moon and John Entwistle, God rest their souls, were reportedly very close, and this clip from a London Coliseum show in 1969 is reliable evidence that they were 100% platonic, for sure. Roger talks today about how he sees photos from 1967 and thinks that was my sister. Giving me, an opportunistic writer with an (over)active imagination, a gold mine to, um, mine.

That fanfiction I mentioned a while back? Yep. Except it isn’t ‘I’m sleeping with them’ like I’ve written for other bands/artists, it’s ‘they’ve def slept with one another, let’s picture when and how.’ What can I say, they expand my horizons.

It isn't just the vibes that get me going, it's the music too. Well, some of it. Longtime beacon Wesley Stace once wrote “I can have sex to Joe Tex and Who’s Next”—followed by “but I can’t make love to Bob Dylan”—and kudos to him if that’s true, because I would feel like I was inside a video game with all the bleep-bloops. Who’s Next can really only be a running soundtrack for me, as I’ve said. (What do you want from me with a lyric like “I’m gonna run and never stop.”) It’s very cerebral, and I need space to concentrate on it, which, incidentally, is Wes’s point about Dylan. But you all know how I feel about him.

Speaking of photos from 1967, that's what I thought the above was at first, as it resembles the band's two appearances that year on the Hamburg-based program Beat-Club. (Turns out it's from the short-lived but influential Ready Steady Go! the previous year. The signage is a clue, but I found it in a German Zeitung, so. Kind of misleading.) Hamburg was by then an inevitable destination for British pop groups. The song selection they performed over those two spots, from "Pictures of Lily" to “Heat Wave” (a girl-group nod) to the one we're about to get into, would have challenged any kid's notions of gender roles.

***

“I’m a Boy” was released as a single on 26 August 1966. In an interview with Melody Maker, John called it “almost a queer song.” I, going on sixty years later, was shook. Among the million thoughts that entered my brain at once were this scene from 30 Rock and this one from Modern Family. I have since sorted through the remaining thoughts in the hopes of being able to offer some insight.

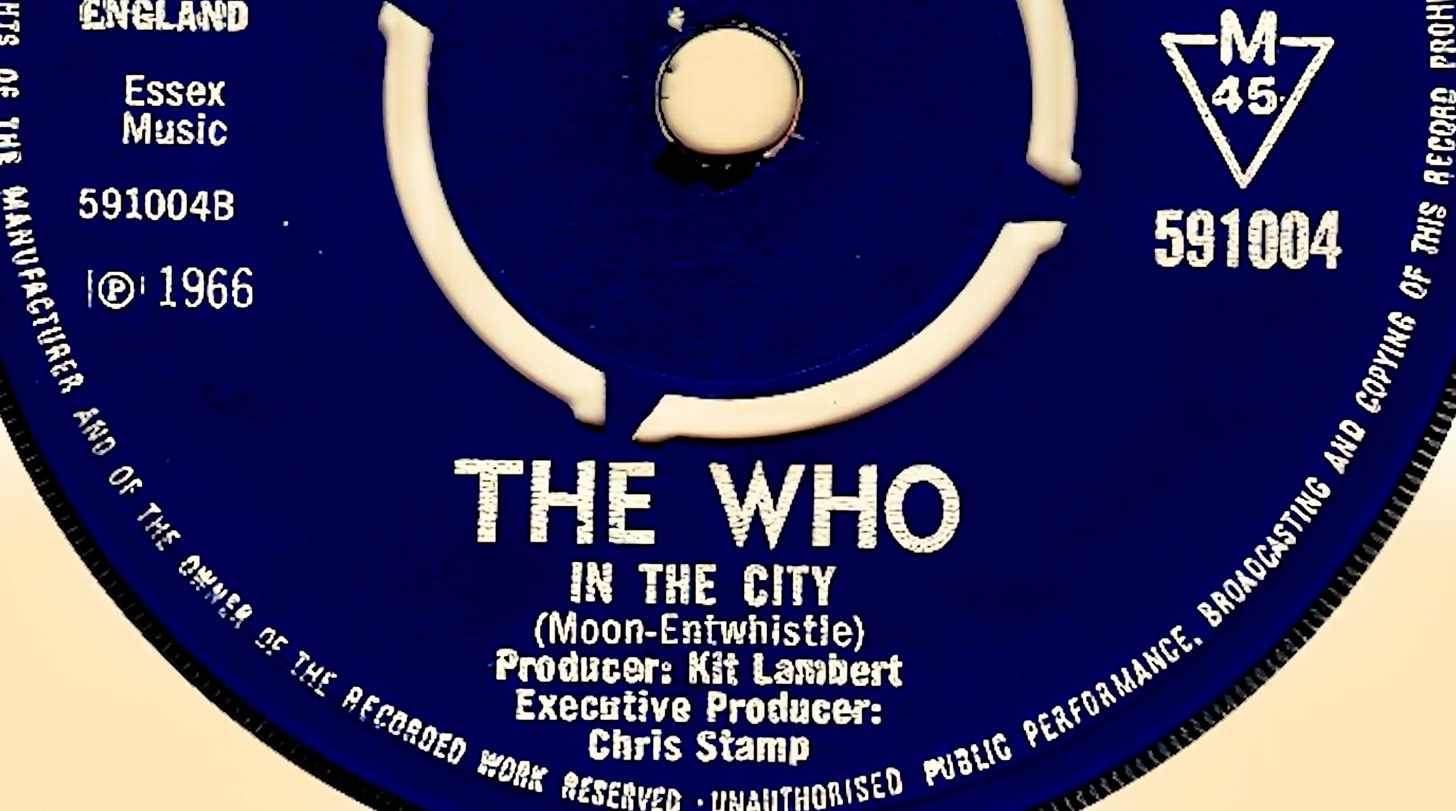

“In the City,” the B-side and the only composition credited to Moon-Entwistle, did well in Germany and Britain and can be found on reissues of A Quick One (their sophomore LP, released in December of that year). “I’m a Boy” does not appear on those reissues, nor does it need to when most compilations include it.

The single went to #2 in the UK and #1 in Melody Maker’s in-house charts, their biggest hit to date. Between the praise lavished on the instrumentals and the comparison of the harmonized oohs in the break to something Brian Wilson might compose, the reviews were enthusiastic all around:

But the version I first heard is not the single, rather the alternate take that rounds out the collection Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy, which, in mid-’71, sectioned off the singles-dominated early years from the future heralded by Who’s Next. It is one of the greatest singles collections I have heard in my short life. The joint force of its fourteen tracks rivals the Beatles’ 1. Except none of them hit #1 on the charts, because the most influential music is not always the most commercially successful.

This alternate take, at 3:41, has a full minute on the single. It features an extra verse and an extended break, minus Wilsonian oohs but plus Entwistle horn. It gives the performances room to breathe. And yet the journey was a dense one for an unprepared listener to undertake, even in a more accommodating time frame.

It was meant to be part of a still longer, denser journey. The original Townshend opera idea, Quads, focused on a family in a society where the gender of potential children can be selected. (A second conceptual track, “Disguises,” is another standout.) The parents ‘order’ four girls but mistakenly receive three girls and a boy, whom they prevail upon to present and behave as another girl. This song is his assertion of self-knowledge and his cry for help.

On the single, Pete sings the expository bits of the verses, suggesting a Greek chorus. The alternate version is sung entirely by Roger, which I prefer because even he subtly differentiates the voices of the limited narrator in distress, his demanding, prescriptive mother, and the omniscient narrator holding the scene at arm’s length. Like I said, a lot to pack into a standard-length song.

“My name is Bill and I’m a headcase,” he says—a hilarious introduction, by way of a sort of melodic shouting. Our singer interprets the character to be pretty young, around age eight. But is an eight-year-old being called Bill? Wouldn’t he be Billy, more likely? And his sisters strike me older as well, plaiting their hair and painting their nails as they do. Ah well. Prompts one to reconsider one’s own timeline of initiation into the rituals of girlhood. The ensuing lines provide evocative detail: “I feel lucky if I get trousers to wear / Spend ages taking hairpins from my hair.” Makes one recall one’s own community-theatre nights, filled end to end with bobby pins—and a fair amount of time sans trousers, while we’re at it.

The chorus could be straight out of the 2020s: “I’m a boy, I’m a boy, but my ma won’t admit it / I’m a boy, I’m a boy, but if I say I am I get it.” Clear potential to rile up some people as much as in 1966, if not more so. (On the first chorus of the alternate take, Roger says ‘mother’ instead of ‘ma.’ I am deeply infatuated with the homegrown vibe of this take.) It’s a simple, oddly moving statement. Or perhaps not oddly.

***

Two friends and I recently attended an outdoor screening of Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (1959). It’s a remarkable film, from the script to the performances: we and the crowd were in stitches all night long. The triangular chemistry between Jack Lemmon, Tony Curtis, and Marilyn Monroe is unmatched—save maybe by Olivia Colman-Rachel Weisz-Emma Stone in The Favourite. The writing seemed radical even compared to my first viewing several years ago, let alone compared to its midcentury bedfellows (a word I use intentionally). It is perhaps the forged-identity screwball comedy to end all screwball comedies, but it deals seriously with matters of gender presentation, personal authenticity, and women’s borderline-romantic friendships. There is more emotional honesty among the characters than in many films not involving disguise. The scenes meant to evoke sex, while silly, really are sexy. Curtis’s character, Joe, kisses Monroe’s character, Sugar, in front of a roomful of spectators while still dressed as ‘Josephine.’ No wonder it nearly singlehandedly took down the Hays Code. But the mid-’60s put the final nail in the coffin.

The break on the alternate take is longer and more menacing than it is on the single. The stakes feel higher. This is largely because we stay on the dominant chord the entire time (E major in the key of A major), with none of the chordal resolution, however brief, that those oohs supply. It’s as if we’re holding our breaths for thirty seconds. Pete’s guitar vacillates between tiny interval changes within the E major chord, much like you might find in a Bach prelude. John hops between octaves on his French horn. I imagine our narrator tearing off the wig that’s been imposed on him, weighing up whether to chuck it and face the hostility of his family, ultimately opting for safety.

The mother then gets three extra lines of real estate ordering her daughters about: “Help me wash up, Jean Marie / You can dry, Felicity / Stack the dishes, Sally Joy.” Unlike in the previous verse, our narrator cuts in edgewise at the end. The final verse, the final word, belongs to him: “I wanna play cricket on the green / Ride my bike across the stream / Cut myself and see my blood / I wanna come home all covered in mud.” Here, for a few bars, Keith mimics the famous drum intro to the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby,” a reinforcement of the feminine influence at work even as our narrator dares to voice his desires. On the closing chorus, the triad shifts upward: we’ve had three-part harmony on three choruses now (the single features mostly two-part), but our narrator’s desperation is mounting. “I’m a boy, I’m a boy, but my ma won’t admit it / I’m a boy, I’m a boy, I’m a boy.” He’s reduced to repeating this phrase, pleading to be seen. A sentiment our songwriter was just getting started on.

***

A couple weeks ago on his radio show, my dad played one of Sinatra’s renditions of “Soliloquy,” the number from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical Carousel that finds carousel barker Billy Bigelow musing over the impending birth of his child. “What if he is a girl?” he wonders halfway through, and promptly pivots from picturing the independent exploits of a son (“My boy Bill / I will see that he’s named after me”) to hesitating at the prospect of raising a daughter. “You can have fun with a son / but you’ve got to be a father to a girl.” He grows tender, concerned, determined even to a point of self-loathing as he vows to give her better than the conditions he came up in. He’s filled with a newfound urgency, a desire to fight for her. I wonder how many of the men I know, how many of the men I call friends, have had fathers who fought for them, who learned how to be a father to a boy.

Carousel opened on Broadway on 19 April 1945, to great success. One month later, to the day, Pete Townshend was born.

***

The Beat-Club spot was mimed, of course, to the single. This must have been the context in which I eventually heard the single. It sounded tinny and subdued and badly mixed and half a step lower than the version I was used to—in sum, unnatural—but I tolerated it for the visuals. Roger looking almost priestly with the high jacket collar, Pete with the suspenders. (I’m so into their early wardrobe.) The mirroring of movements: Roger waving his microphone aloft just as Pete lifts his arm to let a chord resonate, a tableau I find as compelling as the windmill. No one seems to think John needs any screen time, as usual, and unjustly. They’re twitching and bopping like any band would in performance, but the impression is not like any band. Why do these motions look so queer in their bodies?

In his video “Am I a Man?”, comedian Chris Fleming imagines—among other scenarios, with trademark breakneck pacing—himself as a confused, curmudgeonly middle-aged dad. “I’m having daughters,” he asides. “No sons. Sons are gross. Every time I see a guy with his son I’m just like, ew, what are you guys, an improv group? Although the one tough thing about having a daughter is knowing that at one point she will hook up with a photographer.”

***

Pete has called his work “music to fight to.” Traditional love songs are not his style. (Nor were they John’s: he used songwriting to confront his fears, such as spiders, and doctors, and his wife.) His lyrics of longing strain toward a more spiritual form of connection; even a tune like “Sunrise,” probably one of the most clear-cut love ballads in the catalogue, confers an ethereal quality on the beloved and dwells on the dullness the narrator finds in his own mind. On the other hand, “Pictures of Lily” depicts two lovers who can never be together because one is, well, a picture, and the other was born several generations too late. We’ve all been there, my dude. Sometimes it’s safer that way.

His characters often don’t know how to relate to their sexuality or don’t think of it (much less of having children of their own) because they’re preoccupied sorting out more basic identity signifiers. Or leading cults. Or getting beat up on the beach. I don’t know these people. But they all represent pieces of their creator’s lived experience. And that reflected on the rest of the band, and we the fanbase are the better for it, seeing ways of coming of age and fashioning a sense of self beyond those that revolve strictly around sexual encounters or the promise of a ‘traditional’ family. (Not an unimportant revelation for an overwhelmingly male fanbase.) They gave expression to these thoughts as probably none of their peer groups was even prepared to. We are granted an alternate take on life through the Who. And I, for one, quite like this alternate take.

My first listen to “I’m a Boy” left me overexcited, feeling I needed to talk to someone about it. But it was nighttime, and I was standing in the middle of my bedroom. What I had for company were the lights in the windows of the apartments across the way. I played it a couple more times through my headphones, mentally put together a three-minute stage production, and looked out my own window, hoping to send up a signal of how my world was being changed. The moment was as quiet as it was big. The rest is history, and history is still happening.

P.S. Cricket? Was that really the occupation of the average boy? I can see Pete’s Google search: what do boys do. (As opposed to mine: pete townshend bisexual???)

Your ending 🥰 “hoping to send up a signal of how my world was being changed” Love! Thank you, Cecilia